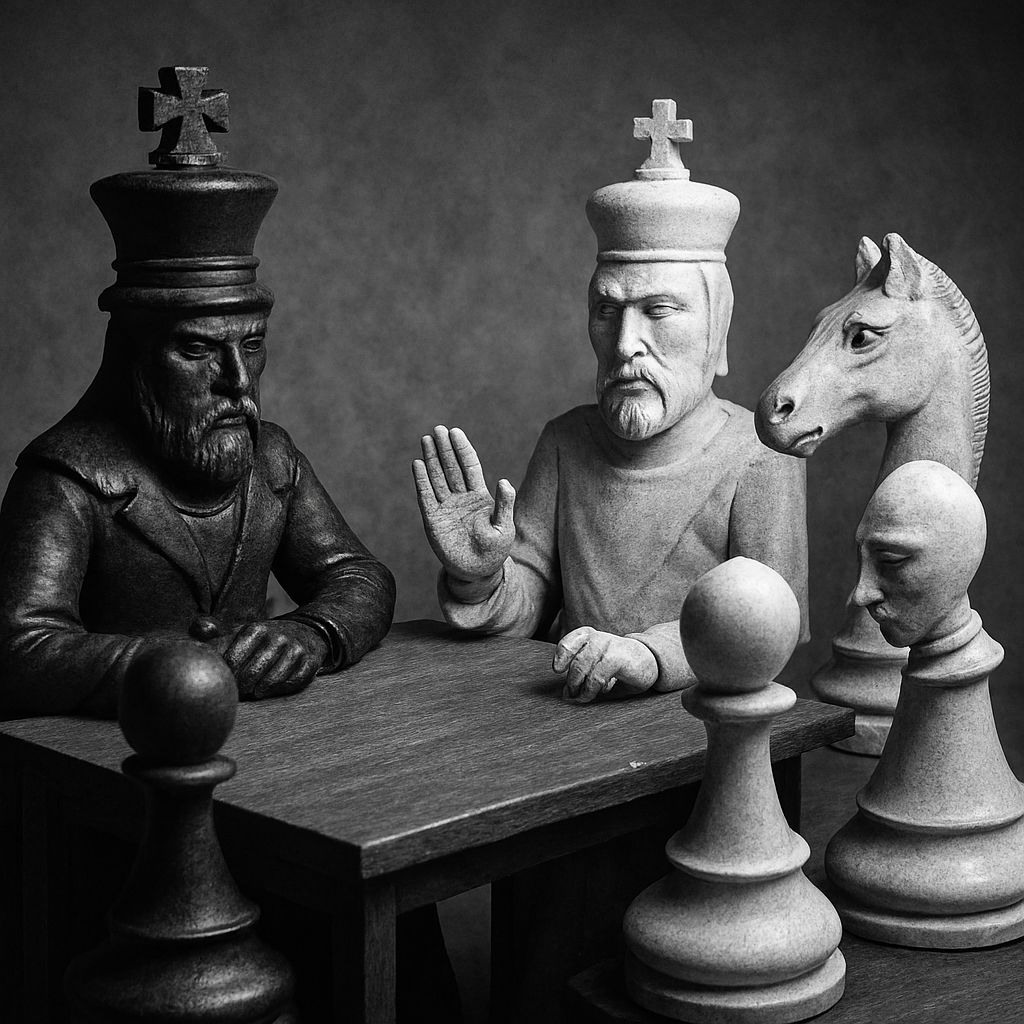

The Perfect Mindful Negotiation Mystical Psychology

Understanding the Mind Negotiation Behind Every Deal

Negotiation is a dynamic psychological process shaped by cognition, emotion, and social context. It involves more than exchanging offers—it requires interpreting intentions, managing affect, and constructing shared meaning. Research in behavioral economics and social psychology shows that negotiation outcomes are heavily influenced by perception and framing. Successful negotiators often rely on emotional intelligence to read subtle cues and regulate their own responses. The process activates multiple brain regions, including the prefrontal cortex for decision-making and the amygdala for emotional salience. Negotiation is recursive—each move reshapes the psychological landscape of the interaction. Trust, power, and identity are constantly negotiated alongside tangible terms. Cultural norms and individual personality traits also shape negotiation styles and expectations. The most effective negotiators adapt their strategies based on feedback and evolving context.

Cognitive Bias and Decision Distortion

Cognitive biases are systematic errors in thinking that affect judgment and decision-making during negotiation. Anchoring bias causes individuals to rely too heavily on initial offers, even when they are arbitrary. Confirmation bias leads negotiators to favor information that supports their preexisting beliefs, distorting objectivity. The framing effect alters perception based on how options are presented—gains versus losses trigger different emotional responses. Loss aversion, a principle from prospect theory, shows that people fear losses more than they value equivalent gains. The endowment effect causes individuals to overvalue what they already possess, making concessions more difficult. Reactive devaluation occurs when proposals are dismissed simply because they come from an opposing party. Overconfidence bias leads negotiators to overestimate their abilities or the strength of their position. Availability heuristic skews judgment based on easily recalled examples rather than statistical reality. These biases are not flaws in logic—they are adaptive shortcuts that can misfire in complex negotiations. Awareness and mitigation of bias are essential for strategic clarity.

Emotional Intelligence and Regulation

Emotional intelligence is the ability and understanding of the ideas of emotional and support that manage emotions in oneself and others. High emotional intelligence enables negotiators to remain calm under pressure and respond constructively to provocation. Empathy allows for deeper understanding of the other party’s motivations and constraints. Self-awareness helps negotiators recognize their emotional triggers and avoid reactive behavior. Emotion regulation strategies—such as cognitive reappraisal—can transform frustration into curiosity or fear into focus. Negotiation often involves emotional labor, especially when stakes are personal or symbolic. Emotional contagion can occur when one party’s mood influences the other’s, consciously or unconsciously. Recognizing microexpressions and tone shifts provides insight into hidden resistance or openness. Emotional intelligence supports rapport-building, which increases trust and cooperation. It also helps negotiators navigate impasse by reframing conflict as a shared problem. In high-stakes scenarios, emotional intelligence is often more predictive of success than technical expertise.

Power and Perception

Power in negotiation is not absolute—it is perceived and context-dependent. Structural power arises from access to resources, alternatives, or institutional authority. Psychological power stems from confidence, presence, and the ability to influence perception. BATNA—Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement—is a key determinant of power, shaping leverage and fallback options. Power asymmetry can lead to coercive tactics or defensive posturing, undermining collaboration. However, perceived power can be enhanced through strategic framing and assertive communication. Research shows that power increases risk tolerance and reduces empathy, which can be counterproductive. Low-power negotiators often use indirect strategies, such as appeals to fairness or coalition-building. Power dynamics are fluid—concessions, revelations, and emotional shifts can recalibrate the balance. Symbolic power, such as moral authority or cultural resonance, can override material disadvantage. Effective negotiators understand that power is relational and must be managed with psychological insight.

Trust and Reciprocity

Trust is the psychological foundation of cooperative negotiation. It reduces uncertainty and enables information sharing, which improves joint outcomes. Trust develops through consistent behavior, transparency, and alignment of interests. Reciprocity—the tendency to return favors—is a powerful mechanism for building trust. Violations of trust trigger strong emotional reactions and can derail negotiations. Trust is multidimensional—cognitive trust is based on competence, while affective trust is based on emotional connection.

Negotiators often use signaling behaviors—such as eye contact or open body language—to convey trustworthiness. Trust repair requires acknowledgment, apology, and behavioral change, not just verbal reassurance. In cross-cultural negotiations, trust norms may differ, requiring adaptive strategies. Game theory models, such as the Iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma, show how trust and reciprocity evolve over repeated interactions. Trust is not static—it must be nurtured and protected throughout the negotiation process.

Framing and Narrative Construction

Framing shapes how negotiation issues are understood and evaluated. It involves selecting and emphasizing certain aspects of reality while omitting others. Gain frames highlight potential benefits, while loss frames emphasize what could be forfeited. Narrative framing embeds facts within emotionally resonant stories, increasing persuasive power. Reframing is a strategic tool to shift perspective and unlock stalled dialogue.

Research shows that people respond more favorably to proposals framed in terms of shared values. Metaphors and analogies can recontextualize conflict and create symbolic bridges. Identity framing connects negotiation to personal or group self-concept, influencing commitment. Temporal framing—short-term versus long-term—affects risk perception and urgency. Negotiators who control the frame often control the agenda and emotional tone. Framing is not manipulation—it is meaning-making, and its ethical use requires clarity and empathy.

Cultural Intelligence and Norm Sensitivity

Culture influences negotiation through norms, values, and communication styles. High-context cultures rely on implicit cues and relational harmony, while low-context cultures prioritize directness and clarity. Individualistic cultures emphasize autonomy and assertiveness, while collectivist cultures value group consensus and face-saving. Time orientation—monochronic versus polychronic—affects pacing and scheduling expectations. Power distance shapes how authority is expressed and challenged in negotiation. Cultural intelligence is the ability to adapt behavior across diverse cultural settings. Misinterpretation of cultural signals can lead to offense or strategic missteps. Rituals and formalities may carry symbolic weight and should be respected. Language barriers require careful use of interpreters and simplified messaging. Successful cross-cultural negotiation requires humility, curiosity, and a willingness to learn from difference.

Identity and Self-Concept

Negotiation activates core aspects of identity, including self-worth, status, and group affiliation. Threats to identity can trigger defensive reactions and reduce flexibility. Identity affirmation—recognizing and validating the other party’s values—can increase openness. Social identity theory explains how group membership influences negotiation behavior and bias. Negotiators may resist proposals that conflict with their self-concept, even if objectively beneficial.

Identity salience varies by context—professional, cultural, or moral identities may dominate. Role expectations shape behavior—leaders, advocates, and mediators negotiate differently. Identity-based conflict requires symbolic resolution, not just material compromise. Negotiators must manage their own identity needs while respecting those of others. Identity is not fixed—it evolves through interaction and reflection. Understanding identity dynamics deepens empathy and strategic insight.

Communication and Listening

Effective negotiation depends on clear, adaptive communication. Active listening involves paraphrasing, summarizing, and validating the other party’s perspective. Nonverbal cues—facial expressions, gestures, posture—convey emotion and intent. Silence can be strategic, creating space for reflection or signaling discomfort. Questioning techniques—open-ended, clarifying, hypothetical—guide exploration and reveal priorities. Tone and pacing influence emotional resonance and perceived sincerity. Miscommunication often arises from assumptions or ambiguous language. Feedback loops—checking understanding and adjusting—enhance clarity and trust. Digital negotiation requires heightened attention to tone and timing due to reduced cues. Communication is not just transmission—it is co-creation of meaning. Skilled negotiators use language to build bridges, not just make points.

Motivation and Goal Alignment

Motivation drives behavior and shapes negotiation priorities. Intrinsic motivation—driven by values or purpose—differs from extrinsic motivation, such as rewards or recognition. Goal alignment increases cooperation and reduces zero-sum thinking. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs suggests that unmet psychological needs can influence negotiation stance. Negotiators often pursue multiple goals—economic, relational, symbolic—simultaneously. Goal conflict requires prioritization and creative problem-solving. Shared goals foster collaboration and expand the negotiation space. Motivation can shift during negotiation as new information or emotional dynamics emerge. Understanding the other party’s motivation enables tailored proposals and empathy. Motivation is not static—it is dynamic and responsive to context. Negotiators must clarify their own goals to avoid drift or compromise fatigue.

Conflict Styles and Resolution

Conflict style influences negotiation strategy and emotional tone. The Thomas-Kilmann model identifies five styles—competing, collaborating, compromising, avoiding, and accommodating. Each style has strengths and risks depending on context and goals. Collaborating seeks win-win outcomes through joint problem-solving. Competing prioritizes assertiveness and control, often at relational cost. Avoiding delays engagement, which can be strategic or evasive. Accommodating prioritizes relationship over outcome, risking self-neglect. Compromising splits difference but may leave deeper issues unresolved. Style flexibility is key—effective negotiators adapt based on feedback and stakes. Conflict escalation can be managed through de-escalation techniques and reframing. Resolution requires both cognitive and emotional work. Conflict is not failure—it is opportunity for growth and clarity.

Ethics and Integrity

Ethical negotiation respects autonomy, transparency, and fairness. Deceptive tactics—such as false concessions or misrepresentation—erode trust and erode long-term credibility. Ethical negotiators disclose relevant information without exploiting asymmetries or ambiguity. Integrity involves honoring commitments and avoiding manipulative framing that distorts mutual understanding. Transparency builds trust and reduces the cognitive load of second-guessing motives.

Ethical behavior is not just moral—it is strategic, as it fosters repeat collaboration and reputational strength. Negotiators must consider the broader impact of their tactics on stakeholders and future interactions. Codes of conduct and professional standards often guide ethical boundaries in formal negotiations. Moral disengagement—justifying unethical behavior through rationalization—can be countered by reflective practice and accountability. Ethics also includes respecting cultural norms and psychological safety. Negotiation is a test of character as much as strategy.

Preparation and Mental Modeling

Preparation is the cognitive scaffolding of effective negotiation. It involves researching facts, anticipating objections, and clarifying goals. Mental modeling—imagining the other party’s perspective—enhances empathy and strategic foresight. Scenario planning allows negotiators to rehearse responses to various outcomes and emotional triggers. Preparation includes understanding the negotiation context—legal, cultural, relational, and symbolic. Cognitive rehearsal activates neural pathways that improve performance under pressure. Visualization techniques can reduce anxiety and increase confidence. Preparation also involves identifying concessions, red lines, and fallback positions. Strategic preparation includes mapping interests, values, and potential trade-offs. The depth of preparation often correlates with negotiation success. It is not just about information—it is about psychological readiness.

Timing and Pacing

Timing influences emotional momentum and strategic leverage in negotiation. Early concessions may signal weakness, while delayed responses can create tension or strategic ambiguity. Pacing affects cognitive processing—rapid exchanges may overwhelm, while slow pacing allows reflection. Temporal framing—urgency versus patience—shapes perceived value and risk. Negotiators often use timing to test commitment or provoke recalibration. Deadlines can increase pressure but also catalyze resolution. Strategic pauses allow for emotional regulation and recalibration of tactics. Time perception varies across cultures and personality types, requiring adaptive pacing. Negotiation is not linear—it unfolds in waves of intensity and reflection. Mastering timing is a psychological skill, not just a logistical one.

Symbolism and Ritual

Symbolism infuses negotiation with emotional and cultural meaning. Rituals—such as handshakes, formal openings, or shared meals—create psychological safety and signal respect. Symbolic gestures, like public acknowledgments or ceremonial agreements, reinforce commitment. Symbols can represent values, identity, or historical context, shaping emotional resonance. In high-stakes negotiations, symbolic acts may carry more weight than material terms. Rituals help structure interaction and reduce ambiguity, especially in cross-cultural settings. Symbolic framing can transform adversarial dynamics into collaborative narratives. Negotiators must be attuned to the symbolic significance of language, setting, and behavior. Ignoring symbolism can lead to misinterpretation or emotional rupture. Symbolism is not decoration—it is a core dimension of psychological engagement.

Adaptability and Feedback

Adaptability is the ability to adjust strategy based on evolving context and feedback. Negotiation is a dynamic system—rigid tactics often fail under pressure. Feedback can be verbal, nonverbal, or situational, requiring nuanced interpretation. Adaptive negotiators monitor emotional tone, shifting priorities, and relational cues. Flexibility does not mean passivity—it means strategic responsiveness. Psychological resilience supports adaptability by reducing fear of failure or rejection. Feedback loops—testing, adjusting, and refining—enhance learning and effectiveness. Adaptability includes recognizing when to escalate, de-escalate, or pivot. It also involves managing internal states—stress, fatigue, and cognitive overload. Negotiators who adapt with integrity and insight often outperform those who rely on fixed scripts. Adaptability is a sign of psychological maturity and strategic depth.

Conclusion

Negotiation is not a mechanical exchange—it is a psychologically rich interaction shaped by emotion, cognition, identity, and context. The most effective negotiators are not just skilled—they are self-aware, empathetic, and ethically grounded. They understand that every offer, pause, and gesture carries symbolic weight. By mastering the psychological dimensions of negotiation, individuals can transform conflict into collaboration and impasse into insight. This post has explored fifteen interwoven layers of negotiation psychology, each offering tools for deeper engagement and strategic clarity. Whether navigating personal relationships or global diplomacy, the principles of psychological negotiation remain universal. They remind us that behind every deal is a human story—complex, emotional, and full of possibility.

Join the Discussion

How do you integrate psychological insight into your negotiation practice – What biases have you encountered – What symbolic gestures have shifted outcomes for you?

#NegotiationPsychology #EmotionalIntelligence #CognitiveBias #StrategicFraming #TrustBuilding #PowerDynamics #SymbolicNegotiation #EthicalStrategy #AdaptiveThinking #ConflictResolution #NarrativeFraming #CulturalIntelligence #IdentityInNegotiation #FeedbackLoops #NegotiationDepth

of course like your web-site but you need to test the spelling on several of your posts. Many of them are rife with spelling issues and I to find it very bothersome to inform the truth however I will definitely come again again.