Jane Goodall – The Powerful Activist Mind Of Environmental Certainty

Jane Goodall – The Legend

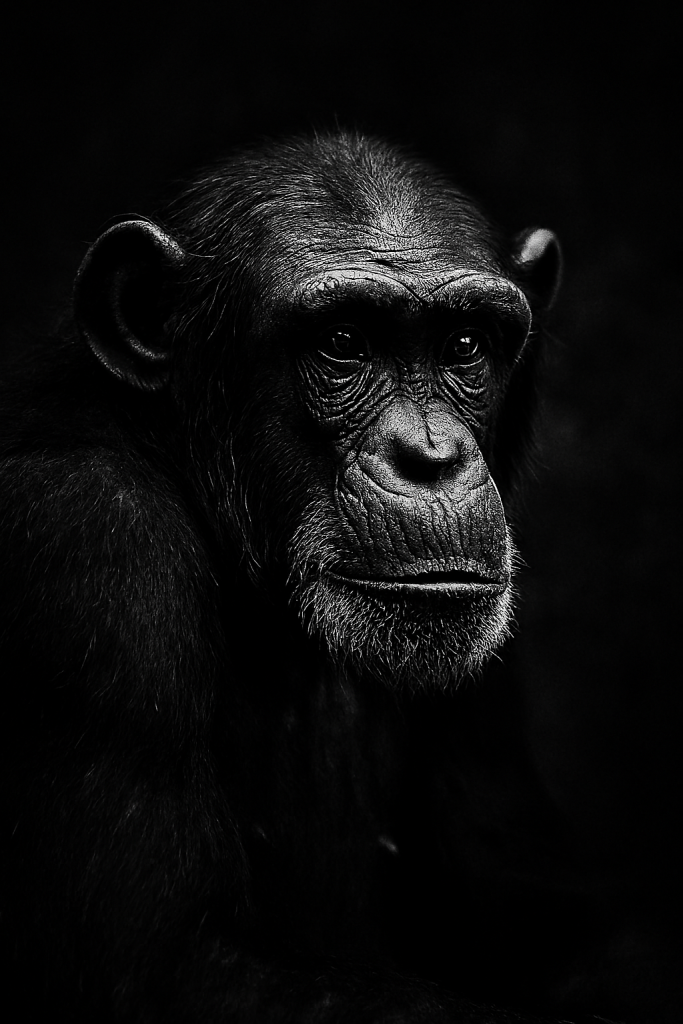

How One Woman’s Psychology Reshaped Humanity’s Bond with Nature

The Untrained Observer Who Redefined Science

Jane Goodall began her scientific career without a university degree, yet she transformed the field of primatology. In 1960, she entered Gombe Stream National Park in Tanzania with a notebook, binoculars, and an open mind. Rather than following rigid scientific protocols, she chose to immerse herself in the daily lives of chimpanzees. She gave individual names to the chimpanzees she studied, which was considered unorthodox at the time. Her method emphasized trust-building and long-term observation, allowing her to witness behaviors others had missed. This approach led to the groundbreaking discovery that chimpanzees use tools, a behavior previously thought to be uniquely human.

Her findings challenged the prevailing belief that tool use was a defining trait of humanity. Initially, her work was met with skepticism by the scientific establishment, but it was later validated through peer-reviewed studies. Goodall’s lack of formal training allowed her to observe without the constraints of academic bias. Her psychological framework was built on empathy, patience, and a deep respect for animal consciousness.

Childhood Roots of Empathy

Jane Goodall was born in Bournemouth, England in 1934, and her early years were shaped by a profound love for animals. Her mother, Vanne Goodall, encouraged her curiosity and never dismissed her questions about nature. As a child, Jane spent hours watching birds and insects, often documenting their behavior in detailed notes. She was captivated by stories like Tarzan and Dr. Dolittle, which inspired her dream of living in Africa. One formative experience involved hiding in a henhouse for hours to observe how chickens lay eggs.

This act of silent observation revealed her natural inclination toward patience and focused attention. Her mother’s support was instrumental in fostering a sense of independence and intellectual freedom. Jane developed an early belief that animals had personalities and emotions, a view that would later shape her research. She saw animals not as objects of study but as beings with intrinsic value and agency. These childhood experiences laid the psychological foundation for her future work in primatology and conservation.

Gombe and the Birth of Ethical Fieldwork

In July 1960, Jane Goodall arrived at Gombe Stream National Park to begin her study of wild chimpanzees. She was sponsored by paleoanthropologist Louis Leakey, who believed her observational skills could yield new insights. Goodall chose to live near the chimpanzees rather than observe them from a distance, breaking with traditional fieldwork norms. She spent months gaining their trust, often sitting quietly for hours without making direct contact.

Her breakthrough came when she observed a chimpanzee named David Greybeard using a twig to extract termites from a mound. This behavior demonstrated that tool use was not exclusive to humans, prompting a reevaluation of human-animal boundaries. She documented complex social behaviors among chimpanzees, including grooming rituals, alliances, and emotional expressions. Her fieldwork emphasized non-invasive methods and prioritized the well-being of the animals she studied. Goodall’s ethical approach influenced future generations of researchers to adopt more humane practices in wildlife studies. Her time at Gombe marked the beginning of a new era in primatology, one rooted in empathy, ethics, and psychological insight.

Tool Use and the Collapse of Human Exceptionalism

Jane Goodall’s observation of chimpanzees using tools was a seismic moment in the history of science. In 1960, she documented David Greybeard modifying twigs to extract termites, proving intentional tool creation. This behavior contradicted the long-held belief that tool use was exclusive to Homo sapiens. Her findings were published in Nature in 1964, sparking global debate among anthropologists and psychologists. The implications extended beyond biology, challenging philosophical definitions of intelligence and culture.

Goodall’s work forced scientists to reconsider the cognitive boundaries between humans and other primates. She demonstrated that chimpanzees not only used tools but also passed techniques through social learning. This suggested the presence of proto-culture, a concept previously reserved for human societies. Her discovery reshaped educational curricula and inspired new research into animal cognition. The collapse of human exceptionalism began with a twig and a termite mound in Gombe.

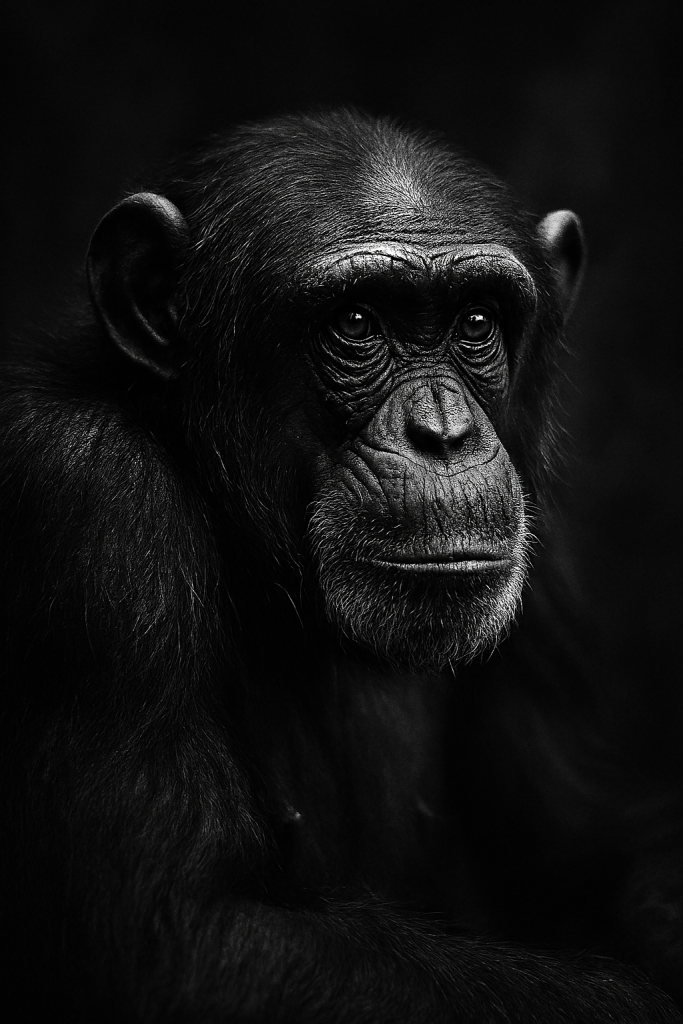

Emotional Intelligence in Chimpanzees

Goodall’s research revealed that chimpanzees possess a rich emotional life, including grief, joy, and empathy. She observed mothers mourning the death of their infants, sometimes carrying the bodies for days. Chimpanzees formed long-term friendships, often grooming and supporting each other during times of stress. Aggression and reconciliation were both part of their social toolkit, mirroring human emotional complexity. Goodall documented instances of altruism, such as food sharing and protection of weaker individuals.

Her findings challenged the notion that emotions were uniquely human or biologically irrelevant. She argued that emotional intelligence was evolutionarily adaptive, not just a cultural artifact. These insights influenced fields like comparative psychology and behavioral ecology. Goodall’s work helped establish the idea that animals have inner lives worthy of ethical consideration. Her observations laid the groundwork for the modern movement toward animal rights and welfare.

The Psychology of Patience and Trust

Jane Goodall’s fieldwork was defined by extraordinary patience and a commitment to building trust. She spent months simply watching chimpanzees from a distance, allowing them to acclimate to her presence. Rather than imposing herself, she let the animals dictate the pace of interaction.

This psychological strategy created a non-threatening environment, essential for authentic behavioral observation. Her quiet persistence allowed her to witness rare and intimate moments in chimpanzee life. She resisted the urge to interfere, even when witnessing distressing events like infanticide or injury. Goodall’s patience was not passive; it was an active form of psychological engagement. She believed that trust was the foundation of ethical science and meaningful discovery. Her methods have since become a model for long-term field studies in primatology and beyond. The psychology of patience and trust became her signature, shaping both her data and her legacy.

Challenging the Scientific Status Quo

Jane Goodall’s methods disrupted the dominant scientific norms of the mid-20th century. She rejected the idea that objectivity required emotional detachment from research subjects. By naming chimpanzees and describing their personalities, she introduced relational science into primatology. Her work was initially criticized for being anecdotal, yet it later became foundational in behavioral studies.

Goodall’s findings were published in peer-reviewed journals, validating her observational rigor. She emphasized narrative clarity alongside data, making her research accessible to both scientists and the public. Her approach inspired a shift toward qualitative analysis in animal behavior studies. She challenged the assumption that animals lacked consciousness or moral agency. Goodall’s work contributed to the rise of interdisciplinary research, blending psychology, anthropology, and ecology. Her legacy continues to influence how science is taught, practiced, and communicated.

The Rise of Conservation Psychology

Goodall’s transition from researcher to activist marked the birth of conservation psychology. She recognized that protecting animals required understanding human behavior and motivation. Her speeches and writings emphasized emotional connection as a driver of ecological action. She founded the Jane Goodall Institute in 1977 to support conservation and education worldwide.

The Roots & Shoots program, launched in 1991, empowers youth to engage in environmental stewardship. Goodall’s activism is grounded in psychological principles like empathy, identity, and moral development. She argues that people protect what they understand and love, not what they fear. Her work has influenced campaigns on deforestation, wildlife trafficking, and climate change. Conservation psychology now includes studies on eco-anxiety, behavioral nudges, and community resilience. Goodall’s influence helped shape this emerging field into a global movement.

Symbolic Thinking in Primates

Goodall’s research revealed that chimpanzees engage in behaviors suggestive of symbolic thought. She observed ritual-like rain dances, where chimpanzees swayed and vocalized during storms. These actions lacked immediate survival utility, hinting at expressive or spiritual dimensions.

Chimpanzees used gestures and facial expressions to communicate complex emotional states. Some individuals showed signs of mourning, including withdrawal and silence after a death. Tool use involved foresight and planning, indicating cognitive mapping and symbolic representation. Goodall documented instances of deception, suggesting theory of mind capabilities. Her findings challenged the binary between instinct and intellect in animal cognition. Symbolic thinking was no longer seen as uniquely human but part of a cognitive continuum. This expanded understanding reshaped debates in philosophy, linguistics, and evolutionary psychology.

25 Factual Insights from Jane Goodall’s Life and Work

- Jane Goodall was born on April 3, 1934, in Bournemouth, England.

- She began her chimpanzee research in Gombe Stream National Park in July 1960.

- Her first major discovery was that chimpanzees use tools, documented in 1960.

- She named her first observed chimpanzee David Greybeard.

- Goodall’s research was funded by Louis Leakey, a prominent paleoanthropologist.

- She earned her PhD in ethology from Cambridge University in 1965 without an undergraduate degree.

- Her 1964 Nature paper on tool use challenged the definition of humanity.

- She founded the Jane Goodall Institute in 1977 to support conservation and research.

- Roots & Shoots, her youth-led environmental program, began in 1991.

- Goodall has written over 25 books, including “In the Shadow of Man” and “Reason for Hope.”

- She was appointed a UN Messenger of Peace in 2002.

- Her work contributed to the ethical reform of animal testing and captivity standards.

- She documented chimpanzee warfare, revealing territorial aggression and coalition tactics.

- Goodall’s observations showed chimpanzees mourn their dead and form lifelong bonds.

- She has received over 50 honorary degrees from universities worldwide.

- Her research influenced the classification of chimpanzees as endangered species.

- She advocates for plant-based diets as part of ecological sustainability.

- Goodall’s lectures emphasize the psychological roots of environmental apathy and action.

- She has spoken at the World Economic Forum and the United Nations.

- Her work inspired the field of conservation psychology and eco-ethics.

- She was awarded the Templeton Prize in 2021 for her spiritual contributions to science.

- Goodall’s methodology is taught in universities as a model of ethical fieldwork.

- She continues to travel over 300 days a year to speak on behalf of animals and the planet.

- Her life has been the subject of multiple documentaries, including National Geographic’s “Jane.”

- Goodall’s legacy is embedded in both scientific literature and global environmental policy.

Global Advocacy and the Psychology of Influence

Jane Goodall’s influence extends far beyond the scientific community. She has spoken in over 100 countries, addressing audiences from schoolchildren to world leaders. Her advocacy is grounded in psychological principles of storytelling, empathy, and moral urgency. Goodall uses personal anecdotes to connect emotionally with listeners, making complex issues relatable. She avoids guilt-based messaging, instead focusing on hope and individual agency.

Her speeches often include calls to action framed around identity and shared values. She understands that behavioral change requires emotional resonance, not just information. Goodall’s influence has shaped global policies on conservation, animal welfare, and sustainable development. She collaborates with NGOs, governments, and grassroots movements to amplify her message. Her psychological insight into persuasion has made her one of the most effective environmental advocates of our time.

Legacy in Education and Youth Empowerment

Goodall believes that lasting change begins with education. She founded Roots & Shoots to empower young people to take action in their communities. The program operates in over 100 countries, engaging students in environmental, humanitarian, and animal welfare projects. Goodall emphasizes experiential learning, encouraging students to observe, reflect, and act. She advocates for curricula that include emotional intelligence, ecological literacy, and ethical reasoning. Her educational philosophy is grounded in respect for all life and the interconnectedness of systems.

She often visits schools, inspiring students with stories from her fieldwork and activism. Goodall’s legacy includes a generation of young leaders committed to sustainability and compassion. Her work has influenced educational policy and teacher training in multiple countries. She continues to mentor youth, believing they are the key to a more ethical and resilient future.

Spiritual Ecology and Moral Imagination

Jane Goodall’s worldview integrates science with spirituality. She often speaks of a “deep spiritual connection” to nature, rooted in awe and reverence. Her experiences in the forest led her to believe in a universal intelligence beyond human comprehension. Goodall’s moral imagination allows her to envision a world where humans live in harmony with other species. She draws on indigenous wisdom, religious teachings, and ecological science to support her vision.

Her speeches often include reflections on gratitude, humility, and the sacredness of life. She believes that spiritual awareness enhances ecological responsibility. Goodall’s integration of ethics and ecology has influenced movements like deep ecology and eco-theology. Her spiritual ecology is not dogmatic but inclusive, inviting people of all beliefs to care for the Earth. This dimension of her psychology adds depth to her activism and broadens her appeal across cultures.

Conclusion

Jane Goodall’s psychological architecture—built on empathy, patience, and moral clarity—has reshaped how humanity sees itself in relation to nature. Her work dismantled the myth of human exceptionalism and elevated the emotional and cognitive lives of animals. She pioneered ethical fieldwork, conservation psychology, and youth empowerment with a visionary blend of science and compassion. Goodall’s influence spans disciplines, generations, and continents, making her one of the most transformative figures in modern history. Her legacy is not just in data or policy but in the hearts and minds of those she has inspired. She taught the world that understanding begins with respect and that science must serve life, not just knowledge.

Her life is a testament to the power of quiet observation and relentless hope. Goodall’s psychology is a blueprint for ethical leadership in an age of ecological crisis. She continues to travel, speak, and mentor, embodying the change she wishes to see. Her story invites us all to listen more deeply—to animals, to nature, and to each other.

Join the Discussion

How has Jane Goodall’s work influenced your view of nature, science, or ethics? Do you believe empathy belongs in scientific research? What lessons from her psychology can be applied to your own field or community?

#JaneGoodallLegacy #EthicalEcology #ConservationPsychology #EmpathyInScience #RootsAndShoots #SpiritualEcology #AnimalConsciousness #SymbolicThinking #YouthForNature #GlobalAdvocacy #EcoLeadership #PrimatologyRevolution #EmotionalIntelligence #ScienceWithSoul #MoralImagination